Project source code at GitHub: lora-mesh

In this project, I will show you how I built a mesh network of 4 Arduino-Based LoRa modules and devised a way to visualize the network’s behavior in realtime. Using a realtime visualization we can see how the network forms and how it heals itself when network nodes become unreachable.

By now you’ve probably heard of LoRa (“long range”) radio technology. It is intended for reliable communication of small amounts of data over long distances (several kilometers). It’s also geared toward low power applications. LoRa modules are relatively cheap (about $8 for a bare module), but the easiest way to use LoRa is to buy development boards that also have a microcontroller on them, like the Moteino.

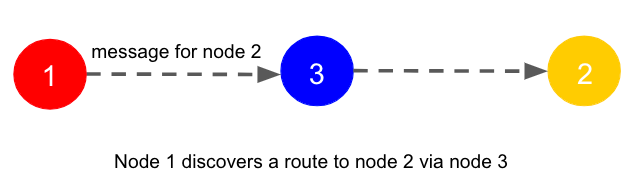

LoRa radios can be used for point-to-point communication, and can also be used in a LoRaWAN network which involves communication with a centralized base station. This article, however, discusses a different approach: mesh networking of LoRa nodes. Mesh networking is a network topology where nodes communicate with one another either directly (if they are in range) or indirectly via intermediate nodes. For example, if node 1 wants to send a message to node 2, but is too far away from node 2, the message will automatically be routed via an intermediate node that is in range, say Node 3.

In fact, the path may involve several intermediate nodes. The discovery of the route from 1 to 2 is handled by a mesh networking layer — your application code doesn’t need to know anything about the routing. With mesh networking, LoRa nodes can be spread out across a further distance but can still communicate with one another as long as there is some connectivity between nodes in the mesh. Every node can talk to every other node, even though the network is only partially connected. Sound familiar? This is pretty much the architecture of the Internet. The robustness lies with the ability to route around damage and find new routes.

Mesh Networking in Arduino Code

How do we accomplish mesh networking with simple LoRa radios? If you have used LoRa radios before, you probably used the RadioHead library. We will use it in this project, too, because it includes an implementation of mesh networking. For details on how the mesh works, see the RadioHead documentation about it. I wrote an Arduino sketch to run on each of 4 Moteino boards so that each node will form a part of the network. Each node has an identity (e.g. “2”) which is stored in the device EEPROM.

First a note about the difficulty of testing mesh networks. It’s hard to place the nodes in such a way that only some nodes can communicate directly. To do so, I’d have to put my nodes far apart all over my neighborhood. Lucky, the RadioHead library has several test networks defined so that you can force some nodes to not be able to communicate. When a test network is defined, the RadioHead library simply ignores messages is receives from nodes it is not supposed to be able to hear. This lets us test much more easily. I’m using test network #3 which is defined in the library like this:

#elif RH_TEST_NETWORK==3 // This network looks like 1-2-4 // | | // --3--

That is, nodes 1 and 4 cannot communicate with one another directly, and nodes 2 and 3 cannot communicate with one another directly. This will become very evident in the visualization.

Each node attempts to communicate with every other node in the network, and in the process it keeps track of a routing table that describes which nodes it can talk to directly and which nodes that messages get routed through when there is no direct connection available. It also keeps track of the signal strength that it “hears” from a node when it communicates with it directly. The result is that each node has a data structure with this info. Here is a sample routing table (expressed in JSON) for node 2:

{"2": [{"n":1,"r":-68}, {"n":255,"r":0}, {"n":1,"r":0}, {"n":0,"r":0}]}

The data has an array of 4 records, one for each node in the network. The 4 records above represent the routing info for this node (2) communicating with nodes 1, 2, 3, and 4 respectively. Each record has two properties. Propery “n” is the identity of the node that node 2 must talk to in order to communicate with the node in this position of the table. Record number 1 {"n":1,"r":-68} means that node 2 can talk to node 1 via node 1. That is, it has successfully communicated directly with node 1 and the signal strength indicated by the “r” property is -68 dBm.

Record 2 {"n":255,"r":0} has an “n” value of 255 which means “self”, so we can ignore this record. Record 3 {"n":1,"r":0} means that node 2 must communicate with node 3 via node 1 because there is no direct communication (which is why the RSSI value is 0). Record 4 {"n":0,"r":0} has a “n” property of 0 which means that node 2 has not yet discovered a way to talk to node 4. This may because it has not tried yet, or perhaps node 4 has dropped out of the network and nobody can find it.

Over time, by attempting to send messages to every other node, each node builds up this information about who it can talk to and how its messages are being routed, as well as the signal strength that it “hears” from any node it successfully communicates directly with. The information sent in messages is the node’s routing table itself. That is why we represent the routing table as a JSON string and use abbreviated property names. We want the message to be short.

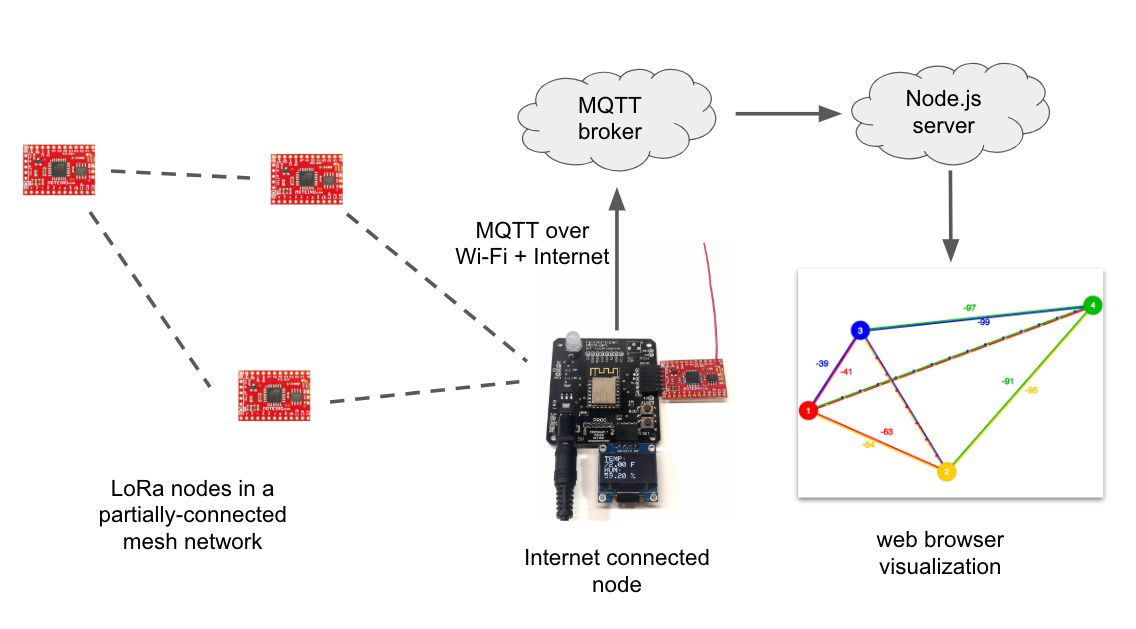

Visualizing the Mesh Network

In order to display the network in a web page, we need to get all the routing information from each node. One of the LoRa nodes in my network (node 1) is connected to the Internet by connecting the Moteino board to an IoT Experimenter board. The IoT Experimenter is a simple ESP8266 development board I built to help with my IoT projects. It serves as a gateway to the Internet for this project. When node 1 receives a routing table from another node, it writes the JSON data over serial to the ESP8266 gateway code. The gateway writes the record to an MQTT topic. Over time, the routing table from each node is written to the topic and updated as the info changes.

Now we need a way for this information to be displayed on a web page. I wrote a Node.js server that subscribes to the MQTT topic and writes the info over a websocket to a web client using Socket.IO. The graphics are created using p5.js which is an easy way to draw impressive graphics on a web page canvas.

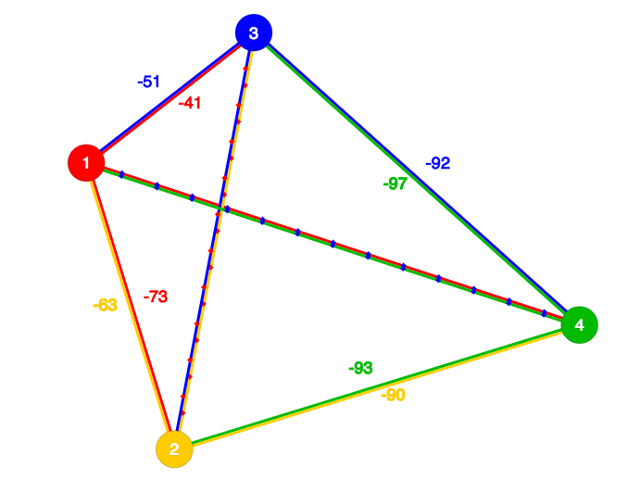

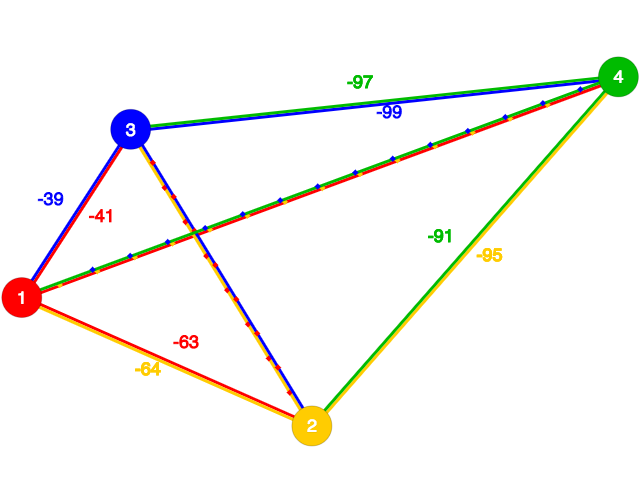

A solid line between 2 nodes means there is direct communication. The color of the line matches the node that is making the observation, and the number is the signal strength that the node “hears” from the other node. So below we can see that node 1 and 2 are directly able to communicate and that node 1 is receiving from node 2 with an RSSI value of -63 dBm and node 2 receives from node 1 with an RSSI of -64 dBm. The distance between nodes is proportional to the signal strength — you can see that node 4 is further away from the other nodes.

Lines with dots indicate indirect communication, for example, the lines between nodes 1 and 4 mean that they are communicating indirectly. The yellow dots on the red line mean that node 1 is communicating with node 4 via node 2 (which is yellow). The blue dots on the green line mean that node 4 is communicating with node 1 via node 3. Note that the communication between nodes 2 and 3 have red dots, meaning that node 1 is serving as the intermediary for these nodes.

Formation/Healing of a Mesh Network

Let’s see the visualization in action! This video shows the formation of a network when I connect power to the nodes. In the video I remove power from one of the nodes serving as an intermediary in the mesh and we can see how the network heals itself by finding new routes.

Get the Code

All the source code for this project is available on GitHub: nootropic design lora-mesh project.

It includes info on how to use this code yourself if you are interested.

hey love project, trying build farm mesh network, long range, to monitor water for sheep, would this code work with esp32 with sx1276 built in

It should work with an ESP32 microcontroller as long as there is also a LoRa transceiver. The RadioHead library does seem to support the ESP32.

I’m trying to implement this with an ESP 32 but I keep getting a Guru meditation error core 1 panic’ed (loadprohibited). exception was unhandled error and sketch\LoRaMesh_modified.ino.cpp.o:(.literal._Z7freeMemv+0x0): undefined reference error for __brkval and __heap_start. Did you encounter the same thing with your ESP 32?

use ESP.getFreeHeap(); instead.

Mrinmoy on February 27, 2020 at 7:45 AM

Hi Michele,

Im going to interface ESP32 with Sx1278 433MHZ… But , at at the point of

manager.sendtoWait((uint8_t*)data, lengt, node)

program halts… Dont know why , same codes working properly with Moteino RM96… but not working with Sx1278 and ESP32 togather …

Can you please suggest me something …

In RHMesh, it shows , should support Semtech Sx1276/78/79

Please help

Sorry, I built my solution only for the modules I have, and cannot explain why the RadioHead library on an ESP32 behaves differently. I did not write the RadioHead library or the mesh networking implementation in that library. I just used the library to show how mesh networking can be visualized.

Amazing project. Which components do you use in end node ? I want to replicate this system. Which lora module you used? Which moteino card you used? Thank you for your reply

I used a Moteino with an ATmega328 microcontroller and an RFM95 transceiver.

Thank you so much Micheal!

Cool project, I’m trying to replicate it as well but I only have 2 LoRa Transceivers.

I managed to initialize void setup() but can’t get the loop to work..

I tried putting some identifiers on which line of arduino code I am at..

I keep getting stuck at this piece of code from void loop():

“uint8_t error = manager->sendtoWait((uint8_t *)buf, strlen(buf), n);”

trying to print “error” but seems like it just won’t show up on the Serial Monitor

I had this error… please be sure that GPIO0 is on pin 2 at the board at least in Arduino nano or pro mini…

Strange, it should return eventually. Did you set the nodeID of each module using the SetNodeId sketch?

Yes I did use the SetNodeId sketch and set it to 1 and 2 respectively for the 2 LoRa modules that I have.

I also set the N_NODES 2 for the LoRaMesh sketch

Hello I have some

Heltec Wifi LoRa 32 – ESP32 with OLED

And try to get it running for days.

I have got many problems.

Is a projeckt known where to go with ESP32 all in one

This project uses the HopeRF RFM95W LoRa radio and the RadioHead library. I do not know if different hardware will work.

Did you happen to get it working? I’m getting this error

Guru Meditation Error: Core 1 panic’ed (LoadProhibited). Exception was unhandled.

Core 1 register dump:

PC : 0x400d0f49 PS : 0x00060d30 A0 : 0x800d1092 A1 : 0x3ffb1f40

A2 : 0x00000002 A3 : 0x3ffbff25 A4 : 0x3ffbff1e A5 : 0x3ffbfdec

A6 : 0x00000001 A7 : 0x00000000 A8 : 0x00000002 A9 : 0x00000001

A10 : 0x00000000 A11 : 0x00000002 A12 : 0x0000000a A13 : 0x00e4c000

A14 : 0x7ff00000 A15 : 0x7ffc9800 SAR : 0x00000016 EXCCAUSE: 0x0000001c

EXCVADDR: 0x00000001 LBEG : 0x400ed478 LEND : 0x400ed495 LCOUNT : 0x00000000

ELF file SHA256: 0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000

Backtrace: 0x400d0f49:0x3ffb1f40 0x400d108f:0x3ffb1f60 0x400d4105:0x3ffb1fb0 0x40089d3d:0x3ffb1fd0

Have you had any luck with heltec esp32 or found any other successful projects?

I looked around for ages for somebody that managed to build a mesh network with lora transceivers. Super amazing that you managed this. No pressure, but if you would be willing to answer some of my projects specific questions, please shoot me an email. It’s a little too long for a comment. I don’t even mind compensating your time. Respect again for your achievements. Really cool stuff

hello, I’m replicating it with some differences I use the esp32 connected by serial port with mega 2560, the mega 2560 has a module lora wifi rfm95 dragino with gps. the gps has not made it work yet. the node.js upload it to a raspberry and the broker configures it in https://api.cloudmqtt.com. the web client charges it and shows me a blank page, I only have two modules working, they are programmed and configured. help help, the broker shows socket error when the esp32 connects.

Hello, I have managed to replicate the project, I have modified it to use node mcu 32s. in my replica I use dragons and two gas sensors. my question is how could I use the gps data and the measurements of the sensors to display them on the same page using the same node.js, with the gps points on a map, sorry for my poor english

Yes, I think you could. You would need to send the GPS coordinates in the LoRa messages. And you would need to find an HTML/JS map component to put on the web page to plot the points. I have not done that, though.

hello victor, I hope you are well, you think you can share your adapted project to mcu 32s in advance thanks.

Hi,

Will this work with Semtech SX1276 module?

Yes, that is the only LoRa chipset. My HopeRF modules have the SX1276 chip on them.

Used shield dragino lora gps with arduino mega 2560are nodes

Hi,

I am trying to replicate the project. Do you have any example test code that I can use?

The very first line of the article points you to the source code.

Thanks for replying Michael. But the source code is not working for me. I am using LoRa SX1276 NiceRF modules. The send2wait is returning no route as error.

Do I need to include the addRouteTo() function in the Arduino Code as well. I can see it is there in the RHRouter class file.

Is there any changes need to be done in the code?

Thanks,

Priti

I did this project with HopeRF modules. I don’t know if the RadioHead library works for NiceRF modules. If you want to use a test network, then yes you need to uncomment one of the network topologies. The article explains this.

hi did you solve this? am having the same issue… help please

Also I see, the sample test networks RH_MESH_TEST_NETWORKS are commented. Do I need to comment out one of them?

Thanks,

Priti

This is a very cool project. How many lora nodes it can support?

Hi Michael,

Thanks for replying. So apart from the network topology option anything else do I need to uncomment in the code?

Sorry I am asking a lot of basic questions here. But your responses means a lot cause I am kinda stuck in here.

I don’t know why it wouldn’t work for you, but again, I did this with HopeRF modules. I don’t know what problems you are having.

So if I do it with hoperf modules, I just need to uncomment the network topology option right. Do I need to make any additional changes in the code?

Setting a test network is not required for communication, but all nodes will be able to hear each other because they are close. Do you have any communication working? Did you set the nodeID of each node in EEPROM?

The project is really interesting and I want to implement it. I was wondering if it is possible to be implemented with Raspberry Pi with Dragino Lora HAT shield and how.

Hi, nice project! I am trying to replicate the project with Esp32 Lora devices. In the updateroutingtable function, routes[n-1] = route->next_hop; line gives a LoadProhibited error. I think it is about the null pointers but couldn’t fix the issue. What might be the cause of route object is created but kept as empty?

Dani, Did you ever solve this on the ESP32, I’ve got the same issue.

hello is a solution of Samuel Archibald

void updateRoutingTable() {

for(uint8_t n=1;ngetRouteTo(n);

Serial.println(routes [ n ]);

if ( route == NULL ){

routes [ n ] = 255 ; // I’m guessing you’re ignoring 255 values?

continue ; // Continue the for loop without executing the if statement

}

if (n == nodeId) {

routes[n-1] = 255; // self

} else {

routes[n] = route->next_hop;

if (routes[n-1] == 0) {

//

rssi[n-1] = 0;

}

}

}

}

Hello, I am also trying this out. Now I’m getting an error that says ngetRouteTo’ was not declared in this scope. What library is it a part of? Help please!!! Thanks :D

The error on the ESP comes from not building the route table before using it.

If you adjust this part in the setup to add some blank routes it should fix it.

manager->clearRoutingTable();

for(uint8_t n=1;naddRouteTo(n, 0);

The error on the ESP comes from not building the route table before using it.

If you adjust this part in the setup to add some blank routes it should fix it.

manager->clearRoutingTable();

for(uint8_t n=1;naddRouteTo(n, 0);

One last try – add after the rssi line

rssi[n-1] = 0;

manager->addRouteTo(n, 0);

Hi Michael,

No, the nodes are not communicating, Somewhere in the recvfromAck function it is getting stuck.

hello, help help,

Hello, I have the project 100% replicated, I am now making changes, but I have problems when sending the GPS data by Lorawan, I am occupying the RadioHead library, the GPS data is recognized as floating, in the Radiohead library is limited to send only 1byte of message, the floating I convert it into an integer multiplying it by 10000 and then I apply an logical one.

int32_t lngi = latid * 10000;

int32_t lati = longi * 10000;

datasend [0] = lati;

datasend [1] = lati >> 8;

datasend [2] = lati >> 16;

datasend [3] = lngi;

datasend [4] = lngi >> 8;

datasend [5] = lngi >> 16;

datasend = latitude and longitude.

how can you change the size payload length ?

help

sorry for the English

Victor, when using the RadioHead library to send a message, you specify the message length in the second argument.

sendtoWait((uint8_t *)buf, length, destination);If using LoRaWAN, things are different. Here is a LoRaWAN project where I send GPS info: https://github.com/nootropicdesign/samd21-lora-gps

Nice project! I’m trying to replicate this project using ESP8266 but this line “routes[n-1] = route->next_hop” keeps reseting the microcontroller. Any thoughts?

I have no idea if this project would work on an ESP8266. Personally, I find the ESP8266 to be quite flakey in a lot of cases, and solid in others.

I’ve got the same issue, i don’t find any solution for that

hello is a solution of Samuel Archibald

void updateRoutingTable() {

for(uint8_t n=1;ngetRouteTo(n);

Serial.println(routes [ n ]);

if ( route == NULL ){

routes [ n ] = 255 ; // I’m guessing you’re ignoring 255 values?

continue ; // Continue the for loop without executing the if statement

}

if (n == nodeId) {

routes[n-1] = 255; // self

} else {

routes[n] = route->next_hop;

if (routes[n-1] == 0) {

//

rssi[n-1] = 0;

}

}

}

}

Comentario

Hello I already tried what Pablo Caol says and it still does not work, the esp8266 is constantly restarted. someone could solve this

Hello,

The reason people keep swearing blind this works and people like you and me are finding out that it doesn’t at first glance, isn’t because they’re wrong, it’s because this message board formats the lower-than symbol and greater-than symbol as html code when they paste their response – thus buggering up their perfectly written code.

At the start of the for loop in the original code when it says

“void updateRoutingTable() {

for(uint8_t n=1;n***LESSTHAN***N_NODES;n++”

Everything after the LESSTHAN symbol this is being cut out of their response.

The fix you need to do, which is what everyone is trying to write; is after the line that reads

” RHRouter::RoutingTableEntry *route = manager-*GREATERTHAN*getRouteTo(n);”

you need to add this:

”

if ( route == NULL ){

routes [ n ] = 255 ;

continue ;

}

”

before the bit of code tat starts “if (n == nodeId) {”

see: https://ibb.co/6NTb46T

The reason for the error is that this function returns a pointer which is becoming null when it doesn’t find a node. AVRs probably just return this as a 0, but the esp is running a sort of operating system which has found a broken bit of code where a pointer points to somewhere in the memory it’s not allowed. Kernels don’t like this and tend to cause segfaults and crash. This Guru meditation error is exactly that. the esp has crashed.

A little bit of error handling fixes this. by setting the null node to 255, you’re giving it an actual hop length of 255 (basically the hop doesn’t exist).

hello, do you think it would be possible to make such a mesh net with many nodes…(200)

for exemple to manage light points in a village. Data would be very simple “on-off”

anyway, your project is very interesting….

Patrick

patrick: 200 nodes would be challenging because the routing tables would be large. You would need to use a microcontroller with more memory than an ATmega328.

Hello Michael, I am trying to implement this project using 4 Adafruit feather m0 nodes (which has a Hoper RFM96). The node is initialized and RF95 is ready but I am getting error of (no route!) plus the route display would look as follows:

14:33:38.432 -> ->2 :[{“n”:255,”r”:0},{“n”:127,”r”:0},{“n”:127,”r”:0},{“n”:127,”r”:0}]

14:33:42.462 -> ! no route

Your feedback will be highly appreciated and Thanks in advance.

Hi Khaled, I would like to try this with Adafruit Feather M0 LoRa boards also. Did you get yours to work?

Is it okay if we use the RN2483 module in this? Because i’m finding a way to make a mesh topology in this module Thanks

I really don’t know. Never used RN2483.

Hello, I am modifying the code in C ++ for Arduino of this project, my question and here I ask for help, in which part of the program I can add the sending of GPS coordinates between them. help I’m starting to program in c ++. I have the Parrot GPS and Mega 2560. The original code works correctly for me.

The function getRouteInfoString is what creates the string to send to the other nodes. You would need to add the GPS info to the buffer. You may not have much room, though. Also, any code that parses the messages (the node.js server) would need to parse out the GPS coordinates. Just study the article so you understand the data format that each node sends to the other nodes and redesign it to include GPS coordinates for the sending node.

Hi, currently considering giving this a try, I currently have 2xArduino Uno so I’ll have to expand with a couple more nodes. Can I use a mix of Moteino and Arduino Uno in a mesh?

Also, which Moteino board do you suggest, is there any point in getting anything other than a standard Moteino with the RFM95 transceiver?

Do your Unos have radios? Each node must have a radio. As for Moteino, you need ones with a LoRa radio, and that means RFM95 transceiver.

Yes, I picked up the Dragino kit not too long ago so I currently have:

1x Ardino Uno w/LoRa Shield

1x Ardino Uno w/GPS+LoRa Shield.

I’ve been using them to roughly map how far the signal can reach from the different spots we’re looking to connect.

In the final build the Arduinos will probably be replaced by Moteinos as well, but would be nice to just pick up 2 or 3 Moteinos with RF95 tranceivers now, and then if I can get it to work get the last 2.

So there is no point in spending the extra $ for the Moteino MEGA for this use? Just this:

https://lowpowerlab.com/shop/product/99

With the RFM95 tranceiver?

Yes, that is the product, yes with RFM95 transceiver.

Thank you.

Does it still use gateway?

No, it’s not LoRaWAN.

i am doing my final year project on LoRa modulation and i am very confused about the coding i don’t know what to do i want to know how to connect multiple pro mini arduino or slaves with the master can any one help me i shall be very thankful for that

This may be a silly question however is the Visualizing side able to display mode than 4 nodes?

When ever I try to add more than 4 all the nodes and connections vanish.

I see one place in the code that seems to assume 4 nodes. Line 46 in mesh.js. Add more colors to this array:

nodeColors = [color('#ff0000'), color('#ffcc00'), color('#0000ff'), color('#00bb00')];Brilliant, thanks. will try that as soon as I get this satellite link operational.

Hi,

Thinking about power consumption, I assume all the nodes in the network must receive continuously, i.e. they cannot go into standby to save battery?

Hi,

would be interested in this,too. @Michael, do you have an answer for this.

Thanks in advance

Hi Michael,

did you also try your project with the encryption of the Radiohead encryption library – RHEncryptedDriver.h?

Thank you very much for your effort – great project.

Peter, I didn’t use any of the encryption in the RadioHead library. It sounds like that explains your payload issues.

It is true that since all nodes are participating in relaying messages for other nodes, it would be difficult to come up with a scheme in which any nodes could sleep. Unless they are all programmed to wake up at some time and send data, then sleep. It is an application-specific problem.

Hi. I have been trying this with with Hope RFM69HCW modules .How did you manage to get the Radiohead Mesh to work with 4 nodes. There is only enough room in the packet for 3 nodes?

I’m not sure why you think that the message won’t fit in the beffer. For LoRa radios the payload is over 250 bytes. You are using a non-LoRa radio witha a different driver. What is your buffer size?

The Hope modules have 60 bytes available with encryption turned on which appears to be the default in the radiohead library for this module. I guess you dont use the encryption facility?

I am using the HopeRF RFM95W LoRa radio. LoRa is an encrypted payload. You are using a non-LoRa radio, the RFM69HCW. That’s a totally different type of modulation, so the RadioHead driver is different. The RFM95W supports a 200+ byte payload in default configuration.

Ok thanks, I am trying to use the standard modules that I already have.

Hi Michael I used a loRa module Ra-01 connected to an arduino nano v3… but the code is telling me that “init failed” at LoRaMesh.ino can you helpme on that? this mean that my radio Ra-01 is not connected well?

22:12:32.843 -> initializing node init failed

22:12:32.941 -> RF95 ready

22:12:32.941 -> mem = 278

22:12:32.941 -> ->2 :[{“n”:255,”r”:0},{“n”:0,”r”:0},{“n”:0,”r”:0},{“n”:0,”r”:0}]

I have not used that radio. I only have used the RFM95W HopeRF radio module.

loRa-02 by Ai-thinker works with your code too! … I was having a wiring issue! now it’s working

hello, please disconnect the Reset pin connected at your Arduino nano.

then it’s working fine Try it.

Hi Michael, Thank you! Great project. I understand NodeId, but is there a NetworkId/MeshId? If I created 2 copies of your project colocated would they conflict with each other? Is there a way to have multiple ‘4 node’ networks/meshes operate independently in the same location? Thanks

There’s no notion of a network ID with LoRa. Just node addresses. If you want separate logical networks, they will need to have non-colliding addresses. You could define a networkId, and then the node address is networkId + nodeId. There would need to be a max number of nodes per network. Node address is a 8-bit number, so only 255 total nodes in a given area.

Do i need to make a mqtt server?

Yes, you will need to use an MQTT server. If you have access to a Linux system, I recommend mosquitto. Also, CloudMQTT offers free MQTT. https://www.cloudmqtt.com/

Thank you! but i am still facing issues in visualising the mesh.

Can you please tell the steps to do it..

I am getting this when i run node.js file

successfully subscribed to topic

{“2”:[{“n”:1,”r”:-44},{“n”:255,”r”:0},{“n”:3,”r”:-13}]}

/Users/surbhikumari/Projects/lora-mesh-master/mesh-server/node_modules/rxjs/internal/util/hostReportError.js:4

setTimeout(function () { throw err; }, 0);

^

ReferenceError: socketClient is not defined

at SafeSubscriber._next (/Users/surbhikumari/Projects/lora-mesh-master/mesh-server/app.js:113:5)

at SafeSubscriber.__tryOrUnsub (/Users/surbhikumari/Projects/lora-mesh-master/mesh-server/node_modules/rxjs/internal/Subscriber.js:205:16)

at SafeSubscriber.next (/Users/surbhikumari/Projects/lora-mesh-master/mesh-server/node_modules/rxjs/internal/Subscriber.js:143:22)

at Subscriber._next (/Users/surbhikumari/Projects/lora-mesh-master/mesh-server/node_modules/rxjs/internal/Subscriber.js:89:26)

at Subscriber.next (/Users/surbhikumari/Projects/lora-mesh-master/mesh-server/node_modules/rxjs/internal/Subscriber.js:66:18)

at MapSubscriber._next (/Users/surbhikumari/Projects/lora-mesh-master/mesh-server/node_modules/rxjs/internal/operators/map.js:55:26)

at MapSubscriber.Subscriber.next (/Users/surbhikumari/Projects/lora-mesh-master/mesh-server/node_modules/rxjs/internal/Subscriber.js:66:18)

at AsyncAction.dispatch (/Users/surbhikumari/Projects/lora-mesh-master/mesh-server/node_modules/rxjs/internal/observable/interval.js:23:16)

at AsyncAction._execute (/Users/surbhikumari/Projects/lora-mesh-master/mesh-server/node_modules/rxjs/internal/scheduler/AsyncAction.js:71:18)

at AsyncAction.execute (/Users/surbhikumari/Projects/lora-mesh-master/mesh-server/node_modules/rxjs/internal/scheduler/AsyncAction.js:59:26)

This error is coming when I uncommented the test data.

Change socketClient to io.sockets so that the events are emitted on the correct object. This bug is due to the fact that I only used the test data when starting the project, so I commented it out.

Same error when running the visualisation script please specify the steps to run the script properly !!!!

You are getting an error because you uncommented code that was not part of the published solution. DON’T be so demanding. This is a project I did for myself and I was generous enough to share all the code and write an article. If you want help, don’t yell at the person that did your work for you.

Change socketClient to io.sockets so that the events are emitted on the correct object. This bug is due to the fact that I only used the test data when starting the project, so I commented it out.

Hi Michael I am writing the reply as you got offended for the language used I am sorry as I think you misunderstood my question due to language .

you have done a great job as no other project describes about Lora mesh and yes it’s your project and it always remain always.

and also thank you for the reply.

and also my intention is not to yell at you again sorry from my side

please accept my apologies.

thank you

It’s Ok, thanks for the note. Please understand that a request with exclamation points (!!!!) is a very aggressive demand in American English.

thanks for understanding Michael ,and also thanks for the solution it worked.

and again sorry for the language

Having difficulty in understanding how the visualisation is done using p5.js because there are no proper documentation for this.

If anyone could suggest me an alternative or the source code for how to draw the mesh network using p5.js, it would be very kind.

Hi,

Will this work with Semtech SX1278 module?

The HopeRF RFM95W module I used has the Semtech SX1278 LoRa chipset.

Hi Michael am using a loRa with SX1278 chipset, I got “! no route” message … do you have any idea why this is happening? is connected to an arduino nano board via SPI and sending data to esp8266 via socket server, thanks bro you are a genius!

did you got the out put . If you could suggest me an alternative. it would be helpful .Thanks in advance

Hi michael,

I am trying to make mesh network for the first time. I read this article. It is so interesting. I have even tested this for two node but i have no idea about forming mesh network. If possible, and if you could guide I need your help on programming side .

But the article describes the whole solution and provides the code.

Hi Michael, great project and very very interesting and I want to apply it. I have some doubts. It can be established that the mesh network is created recently when the modules are for example 500 meters? and that when they are far from the 500mts they are not connected to the mesh? The modules you occupy are compatible with arduino mega?

What I need to do is that when the Arduinos are 500 meters or less their location is sent and thus alert the user.

Will it be possible with more than 10 arduinos with lora? Thank you

Range for LoRa radio communication varies greatly. It can be a several kilometers under good conditions. There is no way to predict range. Arduino Mega can talk to LoRa radio modules. I don’t know if a mesh of 10 modules would work. It all depends on how often you are sending messages. You would need to carefully design your network and communication approach to accomodate that many modules.

Hi Michael, it is a great project and I am very interested in that project. I have a project that is almost similar to the project you are doing, in the project that I am doing, I will track several ships using GPS + LoRa RFM 95 + aduino uno totaling 6 units with 3 pieces of transmitters (LoRa RFM 95 + GPS Ublox neo 6m + Ardunio uno), which I will put on the ship then 2 intermediate nodes (LoRa RFM 95 + Arduino) then 1 receiver / gateway (LoRa RFM 95 + Arduino Uno + Raspberry PI 3 B +).

What I want to ask is what you think of my project? Can Arduino Uno be used as a microcontroller for the LoRa Multi-hop system? Then do you have sample code for Multi-hop (mesh network) systems with LoRa? Or do you have any advice from where I should start learning about this mesh network? because this is new to me.

thank you before

regards

Gomgom

Hi, did you have to make any modifications to the Radiohead library code itself? We’re trying to create a similar LoRa mesh network and having a lot of problems, we think mainly due to collisions and interference.

For example, when node 1 transmits a packet to node 2 all other nodes that hear the packet will immediately attempt to route it; those other node’s transmissions can then interfere with each other and with node 2’s acknowledgement. Node 1 may then fail to see the ack and re-send the packet, which is then routed again by the other nodes etc. The result is a succession of conflicting transmissions that can go on for many seconds (and node 2 can end up receiving and outputting multiple copies of the original packet!).

Hope that makes sense!

No, I did not modify RadioHead. Mesh routing does not mean that the packet is broadcast and everyone who hears it then resends it. The packet will only be sent to one node to forward to another. The RadioHead mesh networking route discovery first figures out which node can handle the packet, and then the packet is sent only to that node. Study the RadioHead mesh code carefully to understand how the route discovery works.

Hi Michele,

Im going to interface ESP32 with Sx1278 433MHZ… But , at at the point of

manager.sendtoWait((uint8_t*)data, lengt, node)

program halts… Dont know why , same codes working properly with Moteino RM96… but not working with Sx1278 and ESP32 togather …

Can you please suggest me something …

In RHMesh, it shows , should support Semtech Sx1276/78/79

Please help

Hi,

I had the same issue on my Heltec WiFi LoRa 32 (ESP32 with SX1276/SX1278).

Replacing these lines:

// Singleton instance of the radio driver

RH_RF95 rf95;

By these lines:

#define SS 18

#define DI0 26

// Singleton instance of the radio driver

RH_RF95 rf95(SS, DI0);

Solved it for me.

I really like this project but I have trouble where to put the code for sending data gathered from sensors. I am just a beginner to this microcontroller thing. Where and what code should I place in order to send data from sensors going to the gateway? Its just a project I want to make at home

The “IoT Experimenter” link in the article, for the ESP8266 development board, just leads back to this page. Is this board available for sale?

Oops, I fixed the link. No, I’m afraid I never brought the IoT Experimenter board to market. Too many cheap Chinese ESP8266 boards out there.

Hi, Michael Its urgent I need to integrate the same thing with FeatherM0 board what I can change in the code as its asking for severaal header files while running the code as I think this code is for ESP8266 board, Please suggest its urgent

Please help me the steps with FeatherM0 board, where to amke changes?

Hii I am using LORAMESH but Faether M0 board, it is not having internal EEPROM. Then what is the alternate?

I dont understand, wouldn’t this break FCC duty cycle of 1% TX? Isnt any Mesh system with LoRa not worth it in the end because the bandwith would be too low for a proper duty cycle?

You are correct that duty cycle can be a problem. It depends on how often you need to send messages across your mesh, and how big the mesh is. If you only need mesh members to send infrequent messages, this can be a useful architecture. But constant communication will exceed duty cycle limits and also result in lots of collisions on the frequency.

void updateRoutingTable() {

for(uint8_t n=1;ngetRouteTo(n);

if (n == nodeId) {

routes[n-1] = 255; // self

}

else {

routes[n-1] = route->next_hop;

if (routes[n-1] == 0) {

// if we have no route to the node, reset the received signal strength

rssi[n-1] = 0;

}

}

}

}

In this function, in the else condition route[n-1] = route->next_hop is causing Exception(28) in Wemos D1 Mini. That exception happens when you try to access a memory location which you shouldn’t access. Any help in resolving this would be appreciated.

Thanks in advance

Hi, Did you ever find a solution to this? It seems all ESP8266’s have the same issue. I’ve got my Lora units running one to another fine but i’d really love this simple mesh to work.

Also the for(uint8_t n=1;ngetRouteTo(n); in your post isn’t right. The brackets aren’t closed for a start. And ngetRouteTo is unkown by the code or libraries. Any thoughts by anyone on how to correct this possible solution?

void updateRoutingTable() {

for(uint8_t n=1;naddRouteTo(n, 0);

}

for(uint8_t n=1;ngetRouteTo(n);

if (n == nodeId) {

routes[n-1] = 255; // self

} else{

routes[n-1] = route->next_hop;

if (routes[n-1] == 0) {

// if we have no route to the node, reset the received signal strength

rssi[n-1] = 0;

}

}

}

}

I’ve just done what everyone else has done – i’ve copied and pasted working code and some interpreter has changed it because of the LOWER THAN character in the second line.

where you see the < (if it happens on your browser, replace it with a lower than character

void updateRoutingTable() {

for(uint8_t n=1; n < = N_NODES;n++) {

routes[n-1] = 0;

rssi[n-1] = 0;

manager- >addRouteTo(n, 0);

}

for(uint8_t n=1;ngetRouteTo(n);

if (n == nodeId) {

routes[n-1] = 255; // self

} else{

routes[n-1] = route->next_hop;

if (routes[n-1] == 0) {

// if we have no route to the node, reset the received signal strength

rssi[n-1] = 0;

}

}

}

}

see: https://ibb.co/6NTb46T